![]() Wir beschäftigen uns in dieser Beitragsserie ausführlich mit dem Ursprung des Cocktails. Wir gehen jeweils auf einzelne wichtige Aspekte ein und fügen sie zu einem Gesamtbild zusammen. Um den Ursprung des Cocktails zu verstehen, sollte man sich anfänglich mit Purl und Stoughton’s Bitters beschäftigen.

Wir beschäftigen uns in dieser Beitragsserie ausführlich mit dem Ursprung des Cocktails. Wir gehen jeweils auf einzelne wichtige Aspekte ein und fügen sie zu einem Gesamtbild zusammen. Um den Ursprung des Cocktails zu verstehen, sollte man sich anfänglich mit Purl und Stoughton’s Bitters beschäftigen.

Aufgrund ihres Umfangs erfolgt die Veröffentlichung dieser Abhandlung über den Ursprung des Cocktails in mehrere Teilen, die sich wie folgt gestalten:

Einleitung

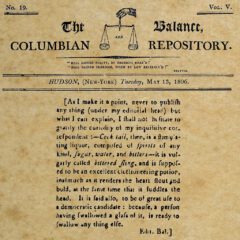

Über die Geschichte und den Ursprung des Cocktails ist schon viel geschrieben worden und wir sind ebenfalls auf die Suche gegangen, um die Ursprünge desselben zu finden. Gemeinhin wird auf die „erste Definition“ des Cocktails aus dem Jahr 1806 eingegangen, und alles wird auf diese Definition zurückgeführt. Auch wir haben bei unserer Recherche damit angefangen. Dabei ist uns jedoch aufgefallen, daß einige wesentliche Quellen teilweise nicht berücksichtigt oder keine Rückschlüsse daraus gezogen wurden. Wir haben versucht, alles in einem Zusammenhang zu sehen und sind dabei auf Erstaunliches gestoßen. Anscheinend ist der Ursprung des Cocktails anders als oftmals beschrieben. In den folgenden Kapiteln werden wir über unsere Funde berichten und tragen die Indizien zu einem schlüssigen Gesamtbild zusammen. Auch haben wir zur Verifizierung etwas experimentelle Archäologie betrieben, mit einem überraschenden Ergebnis.

Wir haben uns lange überlegt, wie man alle Funde übersichtlich miteinander verbindet und sinnvoll präsentiert, und haben uns dafür entschieden, chronologisch vorzugehen und die einzelnen Stränge nach und nach zusammenzuführen.

Wir gehen dabei zunächst auf Purl und Stoughton’s Bitters ein, gefolgt von den einzelnen klassischen Cocktailzutaten. Anschließend betrachten wir die Etymologie der Bezeichnung „Cocktail“ und analysieren vor diesem Zusammenhang historische Rezepte. Es stellt sich dann die Frage, inwieweit der Cocktail ursprünglich als ein medizinisches Getränk zu betrachten ist. Dies führt uns zu den Cocktails, wie sie wohl in England genossen wurden, und zu der Frage, wie diese mit dem Punsch verbunden sind. Anschließend wird die Weiterentwicklung des Cocktails in Amerika kurz betrachtet. Abschließend gehen wir auch noch auf andere Theorien ein, die erklären sollen, wie der Cocktail entstand und zu seinem Namen kam.

Beginnen wir also unseren Ausflug in die Geschichte des Cocktails zunächst mit Purl und Stoughton’s Bitters.

Purl & Stoughton’s Bitters

Um Stoughton’s Bitters besser verstehen und historisch einordnen zu können, müssen wir uns weiter in der Geschichte zurück begeben und uns mit dem „Purl“ beschäftigen. Darunter versteht man heutzutage eine Mischung aus heißem Ale, Gin, Zucker und Ei mit etwas Muskat darüber. [3-210] [6] Doch im 17. Jahrhundert war ein Purl etwas ganz anderes. Er war ein mit Wermut und anderen Drogen infusioniertes Ale oder Bier. Man trank ihn am Morgen, um den Magen zu beruhigen. [3-211] [6] Man trank ihn zur Erhaltung der Gesundheit. Eine alkoholreiche Spirituose wurde nicht zur Herstellung eines Purls verwendet. [3-212]

Wir wissen vom Purl nicht nur von William Shakespeare, sondern finden ihn auch im Tagebuch des Samuel Pepys. [3-211] [19] Dieser war Staatssekretär im englischen Marineamt, Präsident der Royal Society und Abgeordneter des englischen Unterhauses. Bekannt ist er heute vor allem als Tagebuchautor. Seine Aufzeichnungen aus den Jahren 1660 bis 1669 gehören zu den wichtigsten Quellen für diese Zeit im englischen Sprachraum. [11] Samuel Pepys nennt auch eine Version, die Royal Purl genannt wurde, und für die man anstelle von Ale oder Bier einen Sack verwendete. Ein Sack ist ein relativ süßer Sherry, der mit Brandy fortifiziert wurde. Heute würde man diesen Purl Royal wohl als eine Art Wermut klassifizieren. [3-211] [19] Doch wenn man Purl trinken wollte, mußte man ihn sich erst aufwendig zubereiten. Hier bot Richard Stoughton eine Alternative.

Richard Stoughton besaß eine Apotheke in Southwark, heute ein londoner Stadtbezirk. [1] [3-211] [4] [12] [13-162] Zu seiner Zeit begann man damit, vorgefertigte Medizin zu verkaufen, anstatt nach einem Besuch bei einem Doktor eine individuell angefertigte Medizin zu bekommen. So brachte auch Richard Stoughton 1690 sein „Elixir Magnum Stomachicum“ auf den Markt, auch „Stoughton’s Great Cordial Elixir“ genannt. Dieses Elixier schien sich gut zu verkaufen, und Richard Stoughton konnte sich 8 Jahre später in Cambridge zum Studium der Medizin einschreiben. 1712 ließ er sich ein Patent für sein Elixir eintragen. Es war das zweite britische Patent im Bereich der Medizin, [1] [3-211] [12] [13-162] [18] war gültig in England, Wales und für die Stadt Berwick-upon-Tweed und innerhalb des Königreiches Irland, für die Dauer von 14 Jahren. [2]

Die Inhaltsstoffe von Stoughton’s Elixir sind unbekannt. Richard Stoughton selbst gab sie nicht an, nur, daß sie aus 22 verschiedenen Zutaten bestünden, und daß nur er selbst die Rezeptur kenne. Doch Enzian scheint den größten Anteil gehabt zu haben. [1] [3-211] [12] [13-162] Wenn man die Imitate betrachtet, so scheinen wichtige Inhaltsstoffe, über die man sich einig ist, Enzian, Pomeranzenschale und Karmin zu sein, die in Weinbrand eingelegt werden, zusammen mit anderen Gewürzen. [17] [24-695]

In einer Anzeige aus dem Jahr 1710, erschienen am 18. April 1710 in den „Old Bailey Proceedings“ erhalten wir genauere Auskunft über das Elixir, und wozu es verwendet wurde: [3-212] [5]

SToughton’s great Cordial Elixir: Now famous throughout Europe for the Stomach and Blood, as is defended in the Bais with it, prepar’d only by him, Apothecary at the Un in Southwark, set forth 19 Years: It makes the best Purl in Beer or Ale, Purl Royal in Sack, and the better Draught in a Minute, being the best and most pleasant Bitter in the World; now drank by most Gentlemen in their Wine, instead of any other, much exceeding any Bitter made with, which being so excessive hot and drying, thicken the Blood, dulls the spoils the sight, and is well known to recover and restore a weaken’d Stomach or lost Appetite beyond any thing that ever was taken occasioned by hard Drinking or Sickness, &c. and certainly carries off the effects of bad Wine, which too many die of. It has been so incerted in the Bills with It almost 20 years, and the certainty of its doing this, was one of the first Occasions of its being made publick. Sold at the Author’s House, and at many Booksellers and Coffee-houses in and about the City of London; also at some one such place in most Cities and great Towns in Europe at 1 s. a Bottle. Where it is not yet sold, any Person who send first, may have it to sell again with good Allowance, many now selling 50 or 60 Dozen a Year, some more. Ready Mony expected of all. The Seal on each Bottle has Richard Stoughton cut found it, or else ‚tis a Counterfeit.

Wir lesen in der Anzeige, daß Stoughtons Elixir in ganz Europa berühmt sei, um für Magen und Blut Heilung zu verschaffen. Es werde nur von Stoughton, einem Apotheker in Southwark, hergestellt, seit nunmehr 19 Jahren. Mit ihm ließe sich der beste Purl mit Bier oder Ale, und Purl Royal mit Sack innerhalb von einer Minute herstellen. Auch sei es der beste und angenehmste Bitter der Welt. Es werde von Herren getrunken in ihrem Wein und sei wohlbekannt dafür, einen geschwächten Magen zu Kräften kommen und gesunden zu lassen, auch helfe es, wenn der Appetit infolge des Genusses von zu viel Alkohol, durch Krankheit oder infolge anderer Ursachen verloren gegangenen sei. Man nahm das Elixir also auch als Gegenmittel bei einem Kater nach einer durchzechten Nacht. Und das beste daran war, daß man seinen Purl nicht mehr lange vorbereiten mußte, sondern ihn praktisch sofort, innerhalb einer Minute, zubereitet hatte.

Wein gemischt mit Bitter war in Großbritanien und in seinen amerikanischen Kolonien ein gängiges Getränk. Auch George Washington bot es am 6. Mai 1783 seinen Gästen an: [24-163] »Washington zog seine Uhr hervor und stellte fest, dass es fast Zeit zum Abendessen war, und bot Wein und Bitter an.« [25-1162] – »Washington pulled out his Watch & observing that it was near Dinner Time offered Wine & Bitters.« [25-1162]

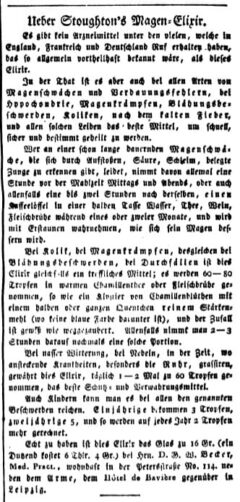

1820 wird Stoughton’s Magen-Elixir im „Intelligenzblatt der Zeitung für die elegante Welt“ wie folgt beworben: „Ueber Stoughton’s Magen-Elixir. Es gibt kein Arzneimittel unter den vielen, welche in England, Frankreich und Deutschland Ruf erhalten haben, das so allgemein vorteilhaft bekannt wäre, als dieses Elixir. In der That ist es aber auch bei allen Arten von Magenschwächen und Verdauungsfehlern, bei Hypochandrie, Magenkrämpfen, Blähungsbeschwerden, Koliken, nach dem kalten Fieber, und allen solchen Leiden das beste Mittel, um schnell, sicher und bestimmt geheilt zu werden. Wer an einer schon lange dauernden Magenschwäche, die sich durch Aufstoßen, Säure, Schleim, belegte Zunge zu erkennen gibt, leidet, nimmt davon allemal eine Stunde vor der Mahlzeit Mittags und Abends, oder auch allenfalls eine bis zwei Stunden nach derselben, einen Kaffeelöffel in einer halben Tasse Wasser, Thee, Wein, Fleischbrühe während eines oder zweier Monate, und wird mit Erstaunen wahrnehmen, wie sich sein Magen bessern wird. Bei Kolik, bei Magenkrämpfen, desgleichen bei Blähungsbeschwerden, bei Durchfällen ist dies Elixir gleichfalls ein treffliches Mittel; es werden 60 – 80 Tropfen in warmen Chamillenthee oder Fleischbrühe genommen, so wie ein Klystier von Chamillenblüthen mit einem halben oder ganzen Quentchen reinem Stärkenmehl (wo keine blaue Farbe darunter ist), und der Zufall ist gewiß wie weggezaubert. Allenfalls nimmt man 2-3 Stunden darauf nochmals eine solche Portion. Bei nasser Witterung, bei Nebeln, in der Zeit, wo ansteckende Krankheiten, besonders die Ruhr, grassiren, gewährt dies Elixir, täglich 1-2 Mal zu 60 Tropfen genommen, das beste Schutz- und Verwahrungsmittel. Auch Kindern kann man es bei allen den genannten Beschwerden reichen. Einjährige bekommen 3 Tropfen, zweijährige 5, und so werden auf jedes Jahr 2 Tropfen mehr gerechnet. Echt zu haben ist dies Elixir das Glas zu 16 Gr. (ein Dutzend kostet 6 Thlr. 4 Gr.) bei Hrn. D. G. W. Becker, Med. Pract., wohnhaft in der Petersstraße No. 114. neben dem Arme, dem Hôtel de Bavière gegenüber in Leipzig“

Wie wir in historischen Rezepten lesen können, trank man zur Erhaltung der Gesundheit seinen Teelöffel Stoughton Bitters – oder einen selbst zubereiteten Ersatz-Bitter – am Morgen oder um 4 Uhr am Nachmittag, und fügte ihn seinem Wein, Tee, Bier oder jedem anderen alkoholischen Getränk hinzu. [7] [8] Auch das originale Stoughton’s Elixir wurde in diesen Mengen zu sich genommen, ungefähr 50 bis 60 Tropfen, die man – einer Anzeige aus dem Jahre 1750 zufolge – „in a glass of Spring water, Beer, Ale, Mum, Canary, White wine, with or without sugar, and a dram of brandy as often as you please“ zu sich nahm, also in einem Glas mit Quellwasser, Bier, Ale, „Mum“, Sack (Sherry), Weißwein, mit oder ohne Zucker, und einer Portion Brandy so oft, wie man mochte. [12] [13-162]

Richard Stoughton starb 1726, und anschließend zerstritt sich die Familie. Sowohl ein Sohn als auch die Witwe eines anderen Sohnes behaupteten beide, als einzige die originale Rezeptur des Elixirs zu kennen. Während sich beide befehdeten, kam noch eine dritte Partei hinzu, die gleiches behauptete: Die Witwe eines Patentbeamten gab an, das Rezept von ihrem Mann bekommen zu haben, der es aus dem Patentantrag gekannt hätte. [13-162]

Unser Versuch

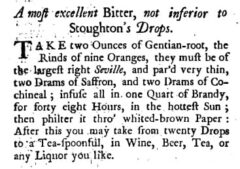

Da die Originalrezeptur von Stoughton’s Bitters nicht bekannt ist, haben wir uns dafür entschieden, eines der historischen Imitate auszuprobieren. Unsere Wahl fiel dabei auf das älteste von uns gefundene, erschienen 1728 in der vierten Ausgabe von Mary Kettilbys Buch „A collection of above three hundred receipts in cookery, physick and surgery“. In der ersten Auflage von 1714 sind sie noch nicht enthalten, die Ausgaben von 1719 und 1724 konnten wir nicht einsehen. Es wird hergestellt aus Enzianwurzel, Orangenschale, Safran und Karmin. Da Karmin geschmacklos ist und somit nur zur Rotfärbung verwendet wird, kann man darauf verzichten. Dadurch vermeidet man auch die darin enthaltenen Allergene. Wir haben uns für dieses Rezept entschieden, weil wir die Zugabe von Safran interessant fanden. Safran bewirkt eine Färbung des Bitters und trägt darüber hinaus auch noch seine Aromen bei. Vermutlich wird man in anderen Rezepten darauf verzichtet haben, da Safran bestimmt schon vor 200 Jahren ein teures Gewürz war. Dennoch wird er in zahlreichen späteren Rezepten verwendet, um ein Imitat der Stoughton’s Bitters herzustellen. Ein weiteres Argument für dieses Rezept ist die Tatsache, daß alle Zutaten auch im originalen Stoughton’s Elixir verwendet wurden. Die Rezeptur aus dem Jahre 1728 ist wie folgt: [15-180]

A most excellent Bitter, not inferior to

Stoughton’s Drops.

TAKE two Ounces of Gentian-root, the

Rinds of nine Oranges, they must be of

the largest right Seville, and par’d very thin,

two Drams of Saffron, and two Drams of Co-

chineal; infuse all in one Quart of Brandy,

for forty eight Hours, in the hottest Sun;

then philter it thro’ whited-brown Paper:

After this you may take from twenty Drops

to a Tea-spoonful, in Wine, Beer, Tea, or

any Liquor you like.

Leider ist das Rezept etwas ungenau. Es werden nämlich zwei Dram an Safran verlangt. Diese Mengenangabe bedarf der Deutung. Es gibt nämlich zwei Möglichkeiten, was unter einem Dram zu verstehen ist. Ein Dram (avoirdupois) entspricht 1,722 Gramm, ein Dram (apothecarius), auch als drachm bezeichnet, entspricht 3,888 Gramm. Letzteres findet Einsatz als Gewicht für Edelmetalle, Medizinalrezepturen und wissenschaftliche Bestimmungen, woher auch der Zusatz „apothecarius“ stammt. [9] Man würde also vermuten, daß in der Rezeptur das Dram (apothecarius) gemeint war. Andererseits sind die übrigen Mengen in Unzen angegeben, und eine Unze entspricht 16 Drams (avoirdupois). [10] Von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus betrachtet, könnte also auch das Dram (avoirdupois) gemeint gewesen sein. Wir haben beides ausprobiert und sind zu dem Schluß gekommen, das das Dram (avoirdupois) für uns richtig ist. Andernfalls werden die Safranaromen zu dominant.

Im Rezept ist die Rede davon, man solle die Schale von zwei Pomeranzen verwenden. Die Frage ist nun: Wieviel ist das? Christian Puszies hat mir die Schale von originalen Curaçao-Orangen überlassen. Nimmt man diese zum Maßstab, so wiegt die getrocknete Schale einer Curaçao-Orange in etwa 15 Gramm. 15 ml getrocknete Enzianwurzel entsprechen ungefähr 7 Gramm; wir werden richtig liegen, wenn wir 7,5 Gramm ansetzen, die Hälfte der Pomeranzenmenge.

Wenn man die Mengen des Originalrezepts verwendet, so stellt man den Bitter her aus 60 ml Enzianwurzel, Schale von 9 Orangen, 1,8 Gramm Safran, 1,14 Liter Cognac. Dies ergibt eine sehr große Menge, und wir haben deshalb heruntergerechnet auf

15 ml getrocknete Enzianwurzel

30 g getrocknete Pomeranzenschale

0,33 Gramm Safran

225 ml Pierre Ferrand Cognac 1840

Man läßt das Gemisch 48 Stunden stehen. Im Originalrezept wird verlangt, daß dies „in der heißesten Sonne“ sein soll, und wir haben es gelegentlich geschüttelt. Anschließend haben wir das Gemisch wie gefordert gefiltert, mit einem Kaffeefilter, und in eine Flasche abgefüllt.

Über das Ergebnis werden wir später berichten, wenn es um die Rekonstruktion eines historischen Cocktails geht. So viel sei vorab berichtet: Das Ergebnis fanden wir überaus köstlich. Bitter, klar strukturiert und mit wundervollen Aromen.

Zur Geschichte der Bitter

Im Zusammenhang mit Stoughton’s Bitters sollte man auch Sydenham’s Bitters erwähnen. Thomas Sydenham lebte vor Richard Stoughton und war ein Wegbereiter für Bitter. Er lebte von 1624 bis 1689, war ein englischer Arzt, der auch als „englischer Hippokrates“ bezeichnet wird. Er eröffnete eine Praxis im Londoner Stadtteil Westminster. [22] [23] Anders als bei den meisten Bitter, deren Hauptaugenmerk auf die Behandlung von Magen- und Verdauungsbeschwerden lag, wurden seine Bitter als Heilmittel gegen Gicht eingesetzt. Thomas Sydenham beklagte die traditionellen Therapien der damaligen Zeit, darunter beispielsweise der Aderlaß, und empfahl stattdessen einen sanfteren Ansatz, der aus einer Ernährungsumstellung, regelmäßiger Bewegung, einer großen Flüssigkeitszufuh und dem Konsum seiner Medizin bestand. Letztere wurden aus Wurzeln von Angelika und echtem Alant, Wermut, Brunnenkresse und Meerrettich. Die darin enthaltenen Bitterstoffe erwiesen sich als ein beliebtes Mittel gegen Gicht. So hat Thomas Sydenham schon vor Richard Stoughton wesentlich dazu beigetragen, Bitter als Medizin anzusehen und einzunehmen. [23]

Quellen

- George B. Griffenhagen & Mary Bogard: History of Drug Containers and Their Labels. ISBN 0-931292-26-3. Madison, American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, 1999. Seite 72. https://books.google.nl/books?id=N4N9bsxc2LYC&pg=PA72&lpg=PA72&dq=stoughton+patent+1712&source=bl&ots=9hZHn-fmRn&sig=TZLAN42-27I0IqkpAQpBk7ODKo8&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwigydKO5J7TAhXF0hoKHR7cAboQ6AEIIjAA#v=onepage&q=stoughton%20patent%201712&f=false

- Bennet Woodcroft: Titles of Patents of Invention, Chronologically Arranged from March 2, 1617 (14 James I.) to October 1, 1852 (16 Vivtoriae). London, 1854. Seite 71. https://archive.org/stream/chronologicalin1617grea_0#page/70/mode/2up/search/stoughton

- David Wondrich: Imbibe! From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash, A Salute in Stories and Drinks to „Professor“ Jerry Thomas, Pioneer of the American Bar. 2. Auflage. ISBN 978-0-399-17261-8. New York, 2015, Seite 313-316. Angegeben wird zusätzlich im Quellenvermerk die Seite im Buch, beispielsweise bedeutet [3-15]: Seite 15.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Borough_of_Southwark: London Borough of Southwark.

- https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=a17100418-1&div=a17100418-1&terms=stoughton#highlight: Old Bailey Proceedings advertisements, 18th April 1710.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purl: Purl.

- 1729 E. Smith: The compleat housewife: or, Accomplished gentlewoman’s companion. 3. Auflage. London, 1729. Seite 248. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=h_ZAAQAAMAAJ&vq=cochineal&dq=editions:OCLC14326985&source=gbs_navlinks_s

- Mary Kettilby: A collection of above three hundred receipts in cookery, physick and surgery: for the use of all good wives, tender mothers, and careful nurses. 5. Auflage. London 1734. Seite 180. https://books.google.de/books?id=OYQEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA180&lpg=PA180&dq=%22Stoughton%27s+drops%22&source=bl&ots=RT_l-SA50L&sig=MZc2kro3D9GKWAwsKloX6rmAnrI&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjxiovT08HTAhWJ0xoKHbZ9ChEQ6AEIQjAF#v=onepage&q=%22Stoughton%27s%20drops%22&f=false

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dram_%28Einheit%29: Dram (Einheit).

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unze: Unze.

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Pepys: Samuel Pepys.

- Craig Horner (Hrsg.): The Diary of Edmund Harrold, Wigmaker of Manchester 1712-1715. ISBN 978-0-7546-6172-6. Hampshire, England & Burlington, USA, Ashgate Publishing, ltd, 2008. https://books.google.de/books?id=f7SGdfGHYwIC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=1712+%22Stoughton%27s+Elixir%22&source=bl&ots=fLCJaq_j91&sig=oTYVCD2GlXAVTNPure6t9Wt03ik&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj4u8mWlvHSAhXWFsAKHWYmCpUQ6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q=1712%20%22Stoughton%27s%20Elixir%22&f=false

- George B. Griffenhagen & James Harvey Young: Old English patent medicines in America. In: United States National Museum, Bulletin 218. Papers 1 to 11. Seite 155-184. Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology. Washington, D. C., Smithonian Institution, 1959. Angegeben wird zusätzlich im Quellenvermerk die Seite im Buch, beispielsweise bedeutet [13-15]: Seite 15. https://archive.org/details/bulletinunitedst2181959unit. Siehe auch http://www.aolib.com/reader_30162_5.htm oder https://archive.org/details/oldenglishpatent30162gut.

- http://www.beeretseq.com/the-cocktails-origin-the-racecourse-the-ginger-part-i/: The Cocktail’s Origin, The Racecourse, The Ginger, Part I. Von Gary Gillman, 30. Januar 2017.

- Mary Kettilby: A collection of above three hundred receipts in cookery, physick and surgery: for the use of all good wives, tender mothers, and careful nurses. 4. Auflage. London 1728. Seite 180. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/10320

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:James_Edward_Alexander00.jpg: Lithograph of James Edward Alexander, 1827.

- Anistatia Miller & Jarred Brown: Die Geschichte des Cocktails. Teil 2. Die kleinen Getränke. In: Mixology 2/2007, Seite 34-37.

- http://www.saveur.com/how-the-cocktail-got-its-name: Ancient Mystery Revealed! The Real History (Maybe) of How the Cocktail Got its Name. Von David Wondrich, 14. Januar 2016.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purl: Purl.

- https://books.google.de/books?id=tYZEAAAAcAAJ&pg=PT11&dq=Stoughtons+elixier&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjIzrOkj6zXAhWKKMAKHa74Bx8Q6AEIrQEwEw#v=onepage&q=Stoughtons%20elixier&f=false Ueber Stoughton’s Magen-Elixir. Intelligenzblatt der Zeitung für die elegante Welt, 3. 29. Februar 1820. Seite 2.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Sydenham_by_Mary_Beale.jpg: Portrait of Thomas Sydenham, Mary Beale, 1688.

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Sydenham: Thomas Sydenham.

- Dr. Adam Elmegirab: Book of Bitters. ISBN 978-1-909313-94-1. London & New York, Ryland Peters & Small Ltd, 2017. Seite 12-13.

- David Wondrich & Noah Rothbaum: The Oxford companion to spirits & cocktails. ISBN 9780199311132. Oxford University Press, 2022.

- https://archive.org/details/ldpd_5800727_005/page/n229/mode/2up?q=%22washington+pulled+out+his+watch%22 I. N. Phelps Strokes: The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 compiled from original sources and illustrated by photo-intaglio reproductions of important maps, plans, views, and documents in public and private collections. New York, 1926.

Rezepte für Stoughton’s Bitters

1728 Mary Kettilby: A collection of above three hundred receipts in cookery, physick and surgery: for the use of all good wives, tender mothers, and careful nurses. 4. Auflage. London 1728. Seite 180. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/10320

A most excellent Bitter, not inferior to

Stoughton’s Drops.

TAKE two Ounces of Gentian-root, the

Rinds of nine Oranges, they must be of

the largest right Sevil, and pared very thin,

two Drams of Saffron, and two Drams of

Cochineal; infuse all in one Quart of Brandy,

for forty-eight Hours, in the hottest Sun;

then philter it through whited-brown Paper:

After this you may take from twenty Drops

to a Tea-spoonful, in Wine, Beer, Tea, or

any Liquor you like.

1729 E. Smith: The compleat housewife: or, Accomplished gentlewoman’s companion. 3. Auflage. London, 1729. Seite 248. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=h_ZAAQAAMAAJ&vq=cochineal&dq=editions:OCLC14326985&source=gbs_navlinks_s

To make Stoughton’s Elixer.

PARE off the Rinds of six Seville Oranges very

thin and put them in a quart Bottle, with

an ounce of Gentian scrap’d and slic’d, and six

pennyworth of Cochineal: Put to it a pint of the

best Brandy; shake it together 2 or 3 times the

first day, then let it stand to settle 2 days, and

clear it off into Bottles for use; Take a large

Tea spoonful, in a Glass of Wine in a Morning,

and at 4 in the Afternoon; Or you may take it,

in a dish of Tea.

1734 Mary Kettilby: A collection of above three hundred receipts in cookery, physick and surgery: for the use of all good wives, tender mothers, and careful nurses. 5. Auflage. London 1734. Seite 180. https://books.google.de/books?id=OYQEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA180&lpg=PA180&dq=%22Stoughton%27s+drops%22&source=bl&ots=RT_l-SA50L&sig=MZc2kro3D9GKWAwsKloX6rmAnrI&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjxiovT08HTAhWJ0xoKHbZ9ChEQ6AEIQjAF#v=onepage&q=%22Stoughton%27s%20drops%22&f=false

A most excellent Bitter, not inferior to

Stoughton’s Drops.

TAKE two Ounces of Gentian-root, the

Rinds of nine Oranges, they must be of

the largest right Seville, and par’d very thin,

two Drams of Saffron, and two Drams of Co-

chineal; infuse all in one Quart of Brandy,

for forty eight Hours, in the hottest Sun;

then philter it thro’ whited-brown Paper:

After this you may take from twenty Drops

to a Tea-spoonful, in Wine, Beer, Tea, or

any Liquor you like.

1736 Anonymus: The complete family-piece: and, country gentleman, and farmer’s best guide : in three parts … : with a complete alphabetical index to each part : the whole, being faithfully collected by several very eminent and ingenious gentlemen, is now first published, at their earnest desire, for the general benefit of mankind. London, J. Roberts, 1736. http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101091222

To make Stoughton’s Elixir.

PARE off the Rinds of 6 Seville Oranges very thin, and

put them in a Quart Bottle, with an Ounce of Gentian

scrap’d and sliced, and six Penny worth of Cocheneal;

put to it a Pint of the best Brandy; shake it together

two or three Times the first Day, and then let it stand

to settle two Days, and clear it off into Bottles for Use.

Take a large Tea-spoonful in a Glass of Wine in a

Morning, and at Four of the Clock in the Afternoon;

Or you may take it in a Dish of Tea.

1739 E. Smith: The compleat housewife: or, Accomplished gentlewoman’s companion. 9. Auflage. London, 1739. Seite 257. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=XvMHAAAAQAAJ&q=stoughton#v=snippet&q=stoughton&f=false

To make Stoughton’s Elixir.

PARE off the rinds of six Seville oranges very thin,

and put them in a quart bottle, with an ounce

of gentian scraped and sliced, and six pennyworth

of cochineal; put to it a pint of the best brandy;

shake it together two or three times the first day,

and then let it stand to settle two days, and clear

it off into bottles for use; take a large tea spoonful

in a glass of wine in a morning, and at four in the

afternoon; or you may take it in a dish of tea.

1746 Mary Kettilby: A collection of above three hundred receipts in cookery, physick and surgery: for the use of all good wives, tender mothers, and careful nurses. 6. Auflage. London 1746. Seite 180. https://archive.org/stream/2691712R.nlm.nih.gov/2691712R#page/n183/mode/2up/search/stoughton

A most excellent Bitter, not inferior to

Stoughton’s Drops.

TAKE two Ounces of Gentian-root, the

Rinds of nine Oranges, they must be of

the largest right Seville, and par’d very thin,

two Drams of Saffron, and two Drams of Co-

chineal; infuse all in one Quart of Brandy,

for forty eight Hours, in the hottest Sun;

then philter it thro’ whited-brown Paper:

After this you may take from twenty Drops

to a Tea-spoonful, in Wine, Beer, Tea, or

any Liquor you like.

1749 Charles Carter: The London and Country Cook: Or, Accomplished Housewife, Containing Practical Directions and the Best Receipts in All the Branches of Cookery and Housekeeping. 3. Auflage. London, 1749. https://books.google.de/books?id=cqNhAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA261&lpg=PA261&dq=%22Stoughton%27s+drops%22&source=bl&ots=30scyq0PsH&sig=qDPfi-dhmUlxzHBvgbkvRGZsEU0&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjxiovT08HTAhWJ0xoKHbZ9ChEQ6AEIRzAG#v=onepage&q=%22Stoughton%27s%20drops%22&f=false

A most excellent Bitter, not inferior to Stoughton’s

drops.

TAKE two ounces of gentian-root, the rinds of

nine Oranges, they must be of the largest right Se-

ville, and pared very thin, two drams of saffron,

and two drams of cochineal; infuse all in one quart

of brandy, for forty eight hours, in the hottest sun;

then philter it through whited-brown paper: after

this you may take from twenty drops to a tea-spoon-

ful, in wine, beer, tea, or any liquor you like.

1755 Elizabeth Cleland: A New and Easy Method of Cookery: Treating, I. Of Gravies, Soups, Broths, &c. II. Of Fish, and Their Sauces. III. To Pot and Make Hams, &c. IV. Of Pies, Pasties, &c. V. Of Pickling and Preserving. VI. Of Made Wines, Distilling and Brewing, &c.Edinburgh, Selbstverlag, 1755. Seite 203. https://books.google.de/books?id=8vQpAAAAYAAJ&dq=%22Stoughton%E2%80%99s+Drops%22&hl=de&source=gbs_navlinks_s

To make Stoughton’s Drops.

INFUSE in a Chopin of French Brandy a Penny-

worth of Cocheneal, a Penny-worth of Snake-root,

half an Ounce of Jamaica Oranges, two Ounces of

bitter Orange-peel, one Ounce of Gentian-root, two

Drachms of Turkey Rhubarb; pound the Rhubarb, Co-

cheneal, and Jamaica Oranges, slice the Gentian; put

them near the Fire for two Days in a strong Glass Bot-

tle; then put the Bottle in a Pan of cold Water, on a

slow Fire: And when it simmers take of the Pan,

and when the Water is cold take out the Bottle, let it

stand two Days; then pour off all that is clear, and you

may put strong Whiskey to the rest, and it will be

good for present Use.

1775 Elizabeth Moxon: English Housewifery. Esemplified in above four hundred and fifty receipts, giving directions in most parts of cookery. … Eleventh edition, Leeds, 1775. Darin der Anhang: A Suplement to Moxon’s Cookery. Seite 27. https://archive.org/details/englishhousewife00moxo/page/26/mode/2up?q=%22orange+bitter%22

To make STOUGHTON.

Take six drams of cochineal beat fine, a

quarter of an ounce of saffron, three drams

of rhubarb, one ounce of gentian cut small,

and the parings of five or six sevile oranges;

to these ingredients put three pints of brandy,

let all stand within the air of the fire three

days; then pour off the liquor, and

fill the bottle again with brandy, putting in

the peel of one or two oranges: Let this

stand six or eight days, then pour it off thro‘

a fine cloth; mix the former and this toge-

ther, and it is fit for use.

1781 John Wesley: Primitive physic: or, an easy and natural method of curing most diseases. 20. Auflage. London, 1781. Seite 118. https://archive.org/stream/b28043522#page/118/mode/2up/search/stoughton

Stoughton’s Drops.

Take Gentian-Root, one Ounce; Cochineal and

Saffron, one Drachm; Rhubarb, two Drachms;

the lesser Cardamom-Seeds, Grains of Paradise,

Zeodary, Snake-Root, of each half an Ounce;

Galengale one Ounce; slice the Roots, and bruise

the Seeds; then infuse them in a Quart of the best

Brandy, and add the Rinds of four Seville Oranges.

When it has stood eight Days, clear it off; and

put a Pint and a half more of Brandy to the same

Ingredients till their Virtue is drawn out. This

is greatly helpful in Disorders of the Stomach.

– See Stomachic Tincture, page 100.

Hinweis: In der 12. Auflage von 1764 stehen die Stoughton Drops noch nicht, auch nicht in der 14. Auflage von 1770.

1795 Sarah Martin: The new experienced English housekeeper, for the use and ease of ladies, housekeepers, cooks, &c. Doncaster, Selbstverlag, 1795. Seite 148. Stoughton Drops. https://archive.org/stream/b21505056#page/148/mode/2up

TAKE the rind of three large seville oranges, peel

them, lay them on a paper and dry them well, take a

quarter of an ounce of gention root when well dried, and

one dram of shred saffron, put them into a wide mouth-

ed bottle, boil a pint of spring water, and a quarter of

a pound of refined sugar, boil it ten minutes, skim it well

when cold, put in a stick of cinnamon and bottle it with

a quart of the best french brandy, shake this every day

for a fortnight, then filter it, fill up your bottle and cork

it.

1796 Samuel Hemenway: Medicine chests, with suitable directions. Salem, 1796. Seite 14. Stoughton’s Elixir. https://archive.org/stream/2556050R.nlm.nih.gov/2556050R#page/n15/mode/1up

This is a good bitter, excellent to create appetite, and

exhilirate the spirits, and to remove weakness and faint-

ness from the stomach. From one to two tea-spoonful

may be taken in a glass of wine, cider, or water, in the

morning at eleven o’clock, and at 5 or 6 in the afternoon.

1799 Major John Taylor: From England To India In The Year 1789. Seite 77. Stoughton’s Elixir. https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.280069/2015.280069.From-England#page/n78/mode/1up

An infusion, or the tincture of bark, gentian,

chamomile, orange-peel, or Stoughton’s

Elixir, used morning and evening are excel-

lent preventative medicines.

1825 Thomas G. Fessenden: The New England farmer. Vol. III. Boston, John B. Russel, 1825. Seite 211. Stoughton’s Elixir. https://archive.org/stream/newenglandfarmer03bost#page/211/mode/1up

Pare off the thin yellow rinds of six large Se-

ville oranges, and put them into a quart bottle,

with an ounce of gentian root scrapped and slic-

ed, and half a dram of cochineal. Pour to these

ingredients a pint of the best brandy; shake the

bottle well, several times, during that and the

following day let it stand two days more to set-

tle; and clear it off into bottles for use. Take

one or two spoonfuls morning and evening, in

a glass of wine, or even in a cup of tea. As a

pleasant and safe family medicine this elixir of

Dr. Stoughton is highly recommended.

1844 G. Girardey: The North American compiler, containing a large number of selected, approved, and warranted receipts. Rossville, G. Girardey, 1844. Seite 29. Stoughton bitter. https://archive.org/details/northamericancom00gira

Stougton bitter. – – – Put 1-2 a pound wormwood, 1-4 of a pound

bitter orange peals, 1 ounce of cascarilla, 1-2 ounce of rhubarb, 2

drachms aloes and 1-4 of wild cherries, with five gallons of rectifi-

ed whisky and 1 gallon of alcohol; let it infuse for 2 months; then

rack it off, and filtrate it through brown paper.

1850 John Wesley: Primitive physic, or, An easy and natural method of curing most diseases. London, Milner and Company, 1850. Darin im Anhang: H. Gifford: The General Receipt Book; or, oracle of knowledge, containing several hundred useful receipts and experiments in every branch of science; with directions of making british wines, &c. London, Milner & Company, ohne Jahr [1850]. Seite 105. Dr. Stoughton’s Stomachic Elixir. https://archive.org/stream/b28123050#page/105/mode/1up/

Dr. Stoughton’s celebrated Stomachic Eli-

xir. — Pare off the thin yellow rinds of six large

Seville oranges, and put them in a quart bottle

with an ounce of gentian root scraped and sliced,

and half a dram of cochineal. Pour over these

ingredients a pint of brandy, shake the bottle

well several times during that and the following

day, let it stand two days more to settle, and

clear it off into the bottles for use. Take one or

two tea-spoonfuls morning and afternoon, in a

glass of wine or in a cup of tea. This is an ele-

gant preparation, little differing from the com-

pound tincture of gentian either of the London

or Edinburgh dispensatories, the former adding

half an ounce of canella alba, (white cinnamon)

and the latter only substituting for the cochineal

of Stoughton, half an ounce of husked andbruised

seeds of the lesser cardamom. In deciding on their

respective merits, it should seem that Stough-

ton’s elixir has the advantage in simplicity,

and, perhaps, altogether as a general stomachic.

Indeed, for some intentions, both the London and

and Edinburgh compositions may have their res-

pective claims to preference; in a cold stomach,

the cardamom might be useful; and, in a laxa-

tive habit, the canella alba. As a family medi-

cine, to be at all times safely resorted to, there

is no need to hesitate in recommending Dr.

Stoughton’s Elixir.

1853 Pierre Lacour: The manufacture of liquors, wines and cordials, without the aid of distillation. Also the manufacture of effervescing beverages and syrups, vinegar, and bitters. Prepared and arranged expressly for the trade. New York, Dick & Fitzgerald, 1853. Seite 283. Stoughton’s Bitters. https://archive.org/stream/manufactureofliq00lacoiala#page/283/

Stoughton’s Bitters. – Water, six gallons; whiskey,

two gallons; gentian-root, three pounds; Virginia

snakeroot, one pound; orange peel, two pounds;

calamus-root, eight ounces; Guinea pepper, twelve

ounces. Infuse the whole of the ingredients in the

two gallons of whiskey for eight days. All solid

substances, viz. roots, plants, &c., &c., should be well

bruised or mashed before adding to the spirit. Color

the above bitters with eight ounces of bruised alka-

net-root.

1853 Pierre Lacour: The manufacture of liquors, wines and cordials, without the aid of distillation. Also the manufacture of effervescing beverages and syrups, vinegar, and bitters. Prepared and arranged expressly for the trade. New York, Dick & Fitzgerald, 1853. Seite 288. Stoughton Bitters. https://archive.org/details/manufactureofliq00lacoiala?q=%22stoughton+bitters%22

Stoughton Bitters, for Making One Gallon. – Gen-

tian, three ounces; Virginia snakeroot, two ounces;

dried orange peel, two ounces; calamus root, half an

ounce; cochineal, one drachm; cardamom seed, two

drachms; whiskey, two pints; bruise or mash the

ingredients, and digest in the spirit for five days, and

strain; then add six pints of water, and bottle for

use.

1861 Daniel Young: Young’s Demonstrative translation of scientific secrets. Toronto, 1861. Seite 55. Stoughton Bitters. https://archive.org/details/youngsdemonstrat00youn

Take of gentian 4oz., orange peel 4oz., columbo

4oz., chamomile flowers 4oz., quassia 4oz., burned

sugar 1lb., whiskey 2 1/2 galls., water 2 1/2- galls.; mix

and let stand one week, then bottle the clear liquor.

1864 Arnold James Cooley: Cooley’s cyclopaedia of practical receipts. processes, and collateral information in the arts, manufactures, professions, and trades, including medicine, pharmacy, and domestic economy. Vierte Auflage. London, John Chichill and Sons, 1864. Seite 555. Stoughton’s Elixir. https://archive.org/stream/b28131423#page/555/mode/1up/

Prep. 1. Raisins (stoned

and bruised), 1 lb.; gentian root, 3/4 lb.; dried

orange peel, 6 oz.; serpentary, 1/4 lb.-; calamus

aromaticus, 1 1/2 oz.; cardamoms, 1/2 oz.; sugar

coloring, 1/4 pint; brandy or proof spirit, 2

gall.; digest a week, and strain.

1864 Jerry Thomas: The Bartenders‘ Guide. Seite 118. Stoughton Bitters.

8 lbs. of gentian root.

6 do. orange peel.

1 1/2 do. snake root (Virginia).

1/2 do. American saffron.

1/2 do. red saunders wood.

Ground to coarse powder; displace with 10 gallons of

4th proof spirit. (See No. 4.)

1868 John Rack: The French wine and liquor manufacturer : a practical guide and receipt book for the liquor merchant being a clear and comprehensive treatise on the manufacture and imitation of brandy, rum, gin and whiskey with practical observations and rules for the manufacture and management of all kinds of wine by mixing, boiling, and fermentation, as practiced in Europe including complete instructions for maufacturing champagne wine, and the most approved methods for making a variety of cordials, liqueurs, punch essences, bitters, and syrups … New York, Dick & Fitzgerald, 1868. Seite 208. Stoughton Bitters. https://archive.org/details/b28061561?q=%22stoughton+bitters%22

12 lbs. dry orange peel,

3 “ Virginia snake root,

1 “ American saffron,

16 “ gentian root,

1 “ red saunders wood.

Grind all the above ingredients to a coarse powder,

and macerate for ten days in 20 gallons alcohol, 65 per

cent; then filter.

Seite 208. Stoughton Bitters. (Another Recipe.)

2 lbs. ginsing,

2 “ gentian root,

“ dry orange peel,

“ Virginia snake root,

1 oz. quassia,

1/4 lb. cloves,

3 oz. red saunders wood,

3 gals. alcohol, 95 per cent,

3 “ soft water.

Grind all the ingredients to coarse powder, and infuse

ten days, and filter.

1869 William Terrington: Cooling Cups andDainty Drinks. Seite 84. American Stoughton Bitters.

16 oz. gentian

root, 12 oz. orange-peel, 3 oz. Virginia snake-root,

1 oz. saffron, 1 oz. red sounders wood; grind

these into a powder; add 1 gallon of rectified spirit;

macerate for three weeks, constantly agitating for

a fortnight; strain carefully; the last pint of

liquor strain separately with pressure, and, when

clear, add it to the clear spirit.

1872 William Terrington: Cooling Cups andDainty Drinks. Seite 84. American Stoughton Bitters.

16 oz. gentian

root, 12 oz. orange-peel, 3 oz. Virginia snake-root,

1 oz. saffron, 1 oz. red sounders wood; grind

these into a powder; add 1 gallon of rectified spirit;

macerate for three weeks, constantly agitating for

a fortnight; strain carefully; the last pint of

liquor strain separately with pressure, and, when

clear, add it to the clear spirit.

1876 Christian Schultz: Manual for the Manufacture of Cordials, Liquors, Fancy Syrups. Seite 118. Bitters, Stoughton.

8 lbs. of gentian root.

6 do. orange peel.

1 1/2 do. snake root (Virginia).

1/2 do. American saffron.

1/2 do. red saunders wood.

Ground to coarse powder; displace with 10 gallons of

4th proof spirit. (See No. 4.)

1891 Anonymus: Wehman’s Bartenders‘ Guide. Seite 81. Stoughton Bitters.

Mix together the following ingredients, and let stand for 5

weeks. Gentian, 4 ounces. Orange peel, 4 ounces, Columbo,

4 ounces. Camomile Flowers, 4 ounces. Quassia, 4 ounces, burnt

Sugar, 1 pound, Whiskey, 2 1/2 gallons. Bottle the clear liquor.

1895 R. C. Miller: The American Bar-Tender. Seite 98. Stoughton Bitters.

8 lbs. of gentian root.

6 do. orange peel.

1 1/2 do. snake root (Virginia),

1/2 do. American saffron.

1/2 do. red saunders wood.

Ground to coarse powder, displace with 10 gallons of

4th proof spirit.

1910 Raymond E. Sullivan: The Barkeeper’s Manual. Seite 45. Stoughton Bitters.

Mix together the following ingredients, and

let stand for five weeks. Gentian, 4 ounces,

orange peel, 4 ounces, Columbo, 4 ounces, camo-

mile flowers, 4 ounces, quassia, 4 ounces, burnt

sugar, 1 pound , whiskey, 2 1/2 gallons. Bottle

the clear liquor.

1912 Anonymus: Wehman Bros.‘ Bartender’s Guide. Seite 76. Stoughton Bitters.

Four ounces of gentian,

Four ounces of orange peel,

Four ounces of columbn,

Four ounces of chamomile flowers,

Four ounces of Quassia,

One pound of burnt sugar,

Two and one-half gallons of whiskey,

Let it stand for five weeks. Bottle the clear liquor.

1912 John H. Considine: The Buffet Blue Book. #192. Stoughton Bitters.

Three-quarter ounce Peruvian bark, 1

ounce wild cherry bark, 2 ounces gentian

root, bruised, 1 ounce dried orange peel, 1

ounce cardamon seeds, bruised. Put In 1

gallon spirits and it will be ready for use

in one week. Strain Into small bottle when

using.

explicit capitulum

*

Abermals toll recherchiert und schön beschrieben. Die nachgeahmte Variante des Stoughton Elixirs klingt zudem wirklich äußerst spannend. Daher bin ich auch gespannt auf Eure weiteren Ausführungen.

Hallo,

ich bin durch Zufall auf eure Seite gestoßen, da ich mir einen Stoughtons zum Probieren gegönnt habe. Also gekauft. Mir scheint es gibt nicht viele Varianten auf dem Markt. Um nicht zu sagen nur einen Einzigen. Interessanterweise sagt der Hersteller, dass ein Dr. Richard Stoughton bzw. „Richard Stovckton“ in der Region um Bockau gewirkt haben soll. Nach einer Rezeptur aus dem 18 Jahrhundert. Wage werden, Enzianwurzel, Angelikawurzel, Zimtrinde, Muskatnuss, Gewürznelken, Kamille (röm.) und eine nicht genauere Farbwurzel genannt. Die Farbe ist dunkel-trüb-violett. Beim Verdünnen soll es grün werden.

Stoughtons war auch in Deutschland mindestens um das 19. Jahrhundert schon bekannt. (https://books.google.de/books?id=tYZEAAAAcAAJ&pg=PT11&dq=Stoughtons+elixier&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjIzrOkj6zXAhWKKMAKHa74Bx8Q6AEIrQEwEw#v=onepage&q=Stoughtons%20elixier&f=false)

Ich vermute aber deutlich eher.

Wer weiß das heute noch genau.

Was mich stutzig macht: Die Farbe. Sollte die nicht rot sein? Und was macht Herr Stoughton im Erzgebirge? 😉

Vielen Dank für diesen interessanten Kommentar! Diesen Bitter müssen wir auch einmal probieren. Die Farbe des „originalen“ Elixirs war rot, und es wird sich bei der sächsischen Alternative sicherlich um eine andere Rezeptur handeln. Wirklich interessant ist, daß ein Dr. Richard Stoughton im 17. Jahrhundert in Brockau als Arzt tätig gewesen sein soll. Hier müßte man sicherlich einmal recherchieren, um zu verstehen, welche verwandtschaftlichen Beziehungen hier bestehen.

Vielen Dank darüber hinaus auch für den Link auf die Zeitung für die elegante Welt Berlin aus dem Jahr 1820 mit der Beschreibung von Stoughton’s Magen-Elixir. Es freut mich immer sehr, neue Quellen kennenzulernen. Diesen Artikel werden wir in unsere Abhandlung einbauen.